How we see the world

Image credit: Tomorrow by Olafur Eliasson. Left: original image, inset containing the lowest-frequency Fourier components used to produce the filtered imagine on the right.

Here is an ostensibly simple question: How do we see the world? In the strictly physical sense, that is. So in what regard, for instance, is an observation done through seeing different from one through smelling or hearing? I started thinking about this a while ago, wrote some stuff down, but did not turn it into a full post until the question came up again last week. I was staying at my parents’ place with my partner, and we were watching reruns of Star Trek with my dad. He’s been fascinated with space exploration since he was young, and given the recent attention on deep-sea environments, it’s not so surprising we ended up discussing deep-sea exploration. Light doesn’t penetrate further than a few hundred yards underwater, and the immense pressure and lack of oxygen make it an environment that may be as adverse to humans as outer space. How, then, does life manage to get by down there? How do fish navigate in the dark? How do dolphins find their food?

While some organisms create their own light through bioluminescence, species have a tendency to finesse the development of other senses if one of them isn’t getting a lot of input – see for instance a shark’s sense of smell1 and an octopus’s sense of touch parallelized over its many suction cups. Impressive as this is, what I’d like to argue is that there is no substitute for vision and (in some cases) hearing, because both senses detect waves, and waves can be imaged, which allows an organism to form an instant spatial representation of its environment.

But what does it mean to image something? Introductory physics classes usually treat imaging of visible electromagnetic radiation (i.e. light) using a lens. The task of such a system is to map an object to an image. We have imaging systems in our eyes, phones, cars, and camera’s, and they’re usually what we think of when asked how we see the world. There are other, quite different, ways of seeing though, and we’ll explore some of them here.

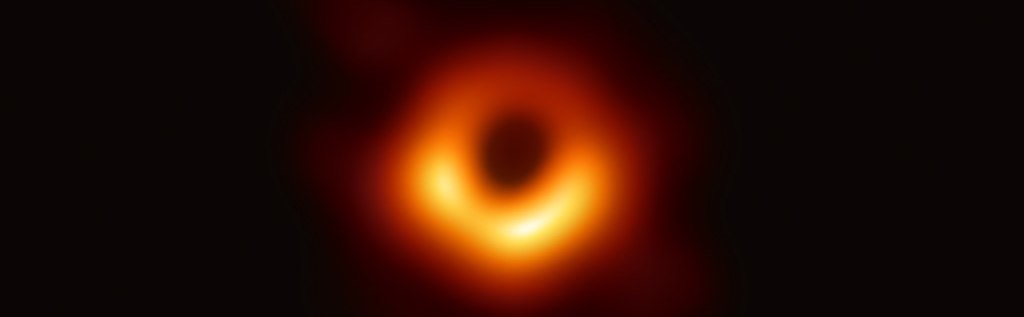

Black holes

Very-long-baseline interferometric (VLBI) telescope image of Messier 87. Courtesy of the European Southern Observatory.

In 2019, astronomers made headlines when they presented the first image ever obtained of a black hole. Consisting of a dark spot surrounded by an orange halo, the photograph showed the black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87 (M87*) – or rather, its shadow – for nothing ever leaves it. This wasn’t simply a matter of pointing a camera in the right direction, but involved a planet-scale collaboration of telescopes. These telescopes didn’t exactly ‘take’ a picture, either, but rather independently measured the same microwave source, and then stitched their measurements together into what looked like a blurry photograph.

None of the individual telescopes ‘saw’ the thing they were looking at, what they did was form an aperture the size of the planet, and instead of using a lens to form an image, they measured the electromagnetic radiation being sent their way from M87*. By synchronizing their measurements using atomic clocks they were able to reconstruct what the image would look like if they were to look at it through an enormous microwave lens. In doing so, they arguably changed what it means to ‘see’ something. This technique is called very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI), since it relies on the phase relation (“delay”) between the different measurements, but the fundamental limits that apply here are the same as those that apply to ordinary imaging.

When imaging something, the ability to tell two points of an object (or equivalently two objects) apart is set by the size of the opening your imaging equipment uses to collect light (the aperture, with diameter $D$), compared to the angle the two points make with respect to the aperture’s center. The larger the aperture, the smaller the angles are that you can resolve, and the better the resolution. This is why substantial telescope dishes are required to tell two celestial objects apart if they’re close to each other but far away from us. This effect arises from the wave nature of light – waves have a tendency to spread out (i.e. to diffract), which makes it impossible to collect all the signal that some source emits using optical systems. Diffraction gets worse as the wavelength $\lambda$ of a wave gets longer, and so we find that the resolution of an image scales as $l\lambda/D$, where $l$ is the distance between the object and the aperture.

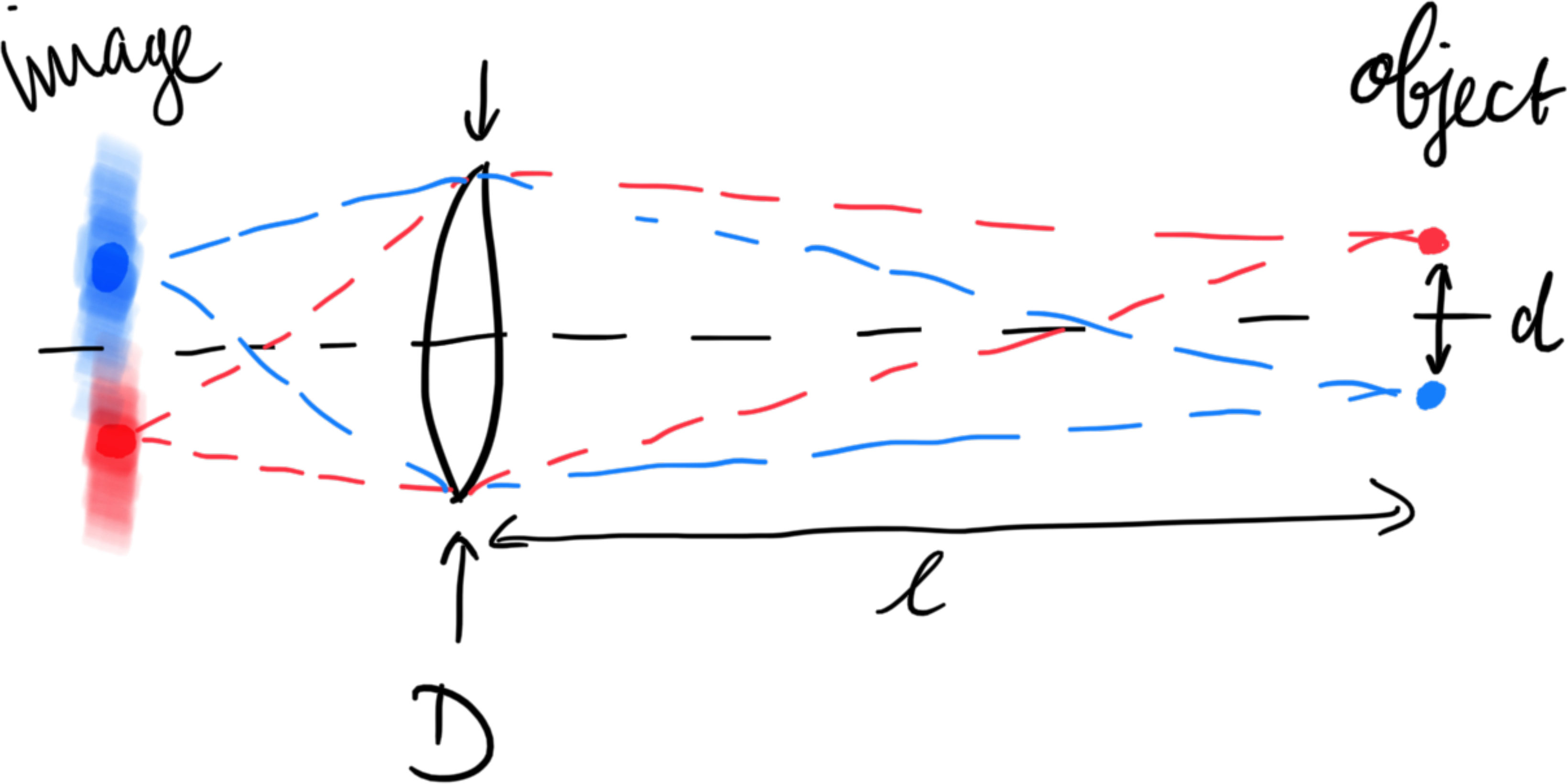

For standard imaging using a lens with diameter $D$ this looks as follows:

Two points (on the right) are imaged (on the left), but develop a blur due to the finite aperture. If the blurs overlap too much we cannot resolve them anymore.

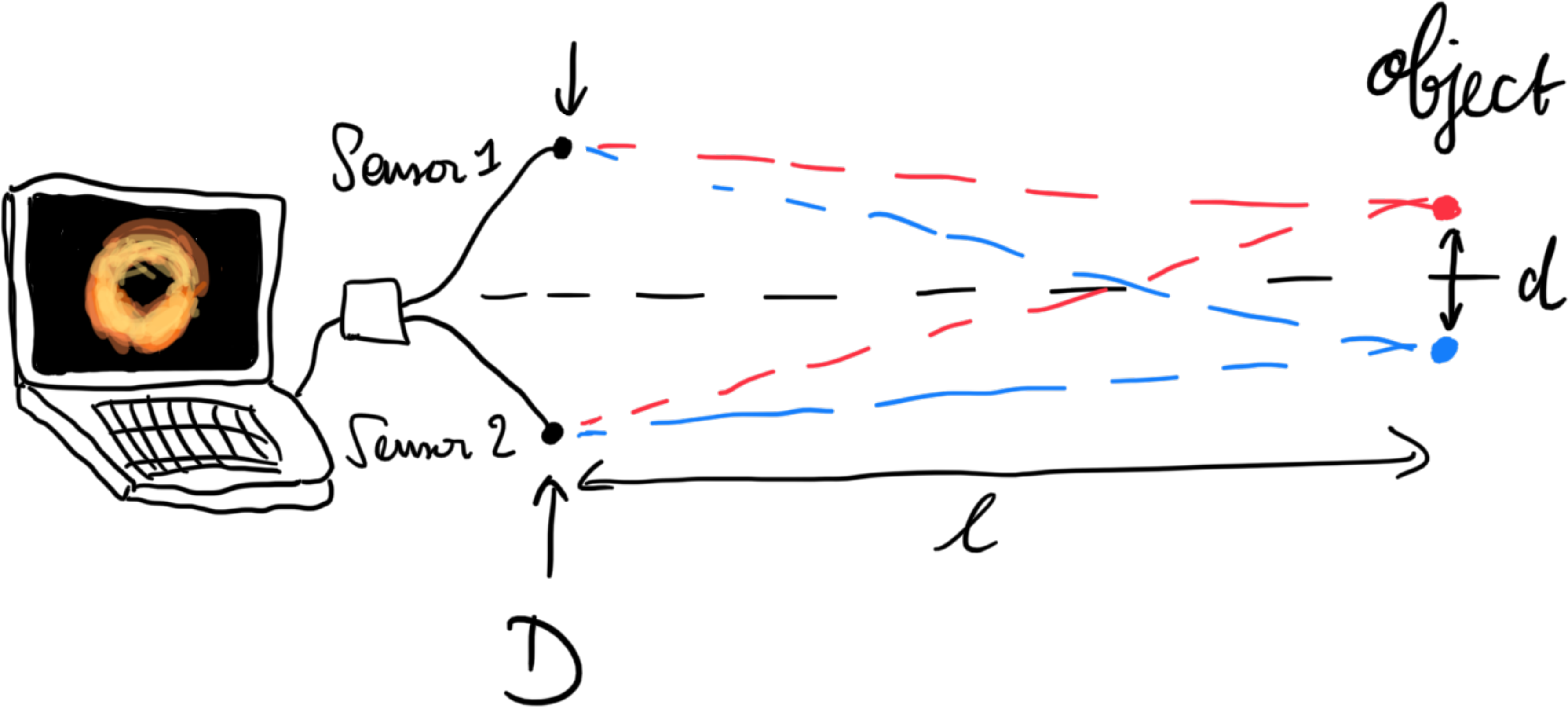

VLBI is different, in that there is no lens. Instead it directly measures the microwave field using antennae or dishes, and then uses an algorithm to combine the signals as if they were imaged using a lens. Schematically:

This approach doesn’t work with visible light since its frequency is too high – we cannot design electronics that respond quickly enough to measure the full electromagnetic wave at optical frequencies. Instead it’s only possible to measure the time-averaged intensity. By using a lens we can, as it were, use physics to sum the wavelets that arrive at the aperture into an image which can be measured as a time-averaged intensity.

So what is the resolution of a VLBI image obtained using the Earth as aperture? To image M87*, they detected 1.3 mm microwaves, which puts the resolution at roughly fifty billion kilometers. M87* is about half that size, so they used some algorithmic tricks to push the resolution beyond its physical limit, resulting in the orange donut.

Echolocation

Sound is also a wave, and so it’s natural to ask whether it’s possible to image it. For us humans, in any case, it will be difficult to do it at the same resolution with which we can image light. Our auditory range starts at 20 Hz and runs up to 20 kHz, which corresponds to wavelengths ranging from 17 m to 17 mm. The aperture size would be limited by the separation between our ears, which is only a few times the shortest wavelength we can hear – this isn’t going to give us a fantastic resolution. But what if we somehow could hear with our hands, which we can spread apart, so as to make the aperture larger? It’d still be a no – the resolution relation given above ($\lambda/D$) is only valid in the limit where the distance between the observer and the object is much larger than the aperture size. It’s not possible to get an arbitrarily fine resolution by making the aperture larger and larger, at that point we run into the fundamental limit of imaging, which states that it’s not possible for the resolution to be finer than a wavelength. In the best case our resolution would be limited to the centimeter scale, which is far, far worse than our eyesight.

So how do bats and other animals that use echolocation do it?

An important difference is that they use 200 kHz ultrasound to locate objects in their vicinity, which they emit themselves. In principle, the shorter wavelength allows them to image at a higher resolution. By using both their ears and by sensing the time delay with which their cries return to both of them, they can get a sense of both distance and direction. This only works because they emit sound at a wavelength of approximately 1.7 mm, which (I suppose) is a few times smaller than the separation between their ears. Were they to use a much lower frequency (or equivalently a longer wavelength) their ears would receive an echo’s that are indistinguishable.2

It’s not possible to ask a bat how it sees the world, but we can take a guess based on some of the fundamental limits we’ve discussed. If it would be 1 m away from some object, it would have a resolution of about 20 cm. It would see a nearby insect as a blob (not unlike our observation of M87*), and this may not sound like much, but in a dark cave this earsight is much more useful than eyesight. It’s interesting to realize how beneficial ultrasound is here, since it would be next to impossible for flying animals to evolve an aperture large enough to use audible frequencies for the same goal.

Thinking about it, it seems like bats use sound in a very similar way as VLBI astronomers use microwaves: they detect the delay in a signal originating from a distant source using their two sensors, which allows them to get a much more detailed map of their surroundings than they would be able to obtain with a single sensor alone.

At this point it can only be expected that aquatic life has evolved echolocation as well, and indeed, dolphins are known to emit ‘clicks’ of high-frequency sound which they can pick up again with their jaws upon reflection. They even have a suspiciously good resolution when they do so, much better than would be expected based on the resolution criterion. It’s still a mystery how they do this, although in principle it’s possible to beat the resolution criterion (by using patterned light in microscopy, for instance). Hypothetically, dolphins could emit patterned sound waves, which would be very impressive indeed. In an interesting experiment,3 researchers put three-dimensional objects into an opaque box which they had a bottlenose dolphin interrogate with its ultrasound. Subsequently, they showed the dolphin different objects, of which it had to choose the one that was inside the box by pushing a paddle. If it chose correctly it got a fish, after which everything would start over. By putting an array of transducers in the box it was possible to measure the echo that was going back to the dolphin, which the researchers used to try and reconstruct how the dolphin was ‘seeing’ through an opaque wall.

It’s clear that studying how animals such as dolphins and bats can ‘see’ in dark environments isn’t just scientifically interesting. Since the wavelengths they use aren’t much smaller than their apertures, their resolution isn’t great, so there’s a tremendous evolutionary pressure to develop superresolution methods. While we humans, in turn, don’t need this for our own eyesight (our pupil diameter is many times larger than optical wavelengths), we have our own ways of extreme imaging, for instance when we look at black holes with VLBI, or when we resolve individual atoms, a few hundred nanometers apart. For these applications it will be very interesting to learn from nature, and to study how species have been able to adapt their ‘imaging systems’ to work beyond the resolution limit. But even if you don’t care about that, seeing a dolphin work out what’s inside a black box is pretty cute.

Footnotes

-

Sharks have separate nasal cavities, which gives them the ability to smell ‘in stereo’ much like we are able to hear in stereo. Therefore they can do something resembling an olfactory finite difference method to calculate the local ‘smell gradient,’ and use it to gradient ascend towards their prey. ↩

-

Curiously, since I’m guessing that a bat’s ear separation is about ten times smaller than a human’s, the ratio of $\lambda/D$ is quite similar for us and them (provided we’re listening at the top of our auditory range). So in principle we would be able to do rudimentary echolocation at 20 kHz, provided we had the hardware on board to measure small delays in the arrival time between our ears. ↩

-

Vishu et al., A dolphin-inspired compact sonar for underwater acoustic imaging, Communications Engineering 1, 10 (2022). Link. ↩