Sinterrandomness

Like many other countries, The Netherlands has an end-of-year tradition that involves getting together in a group and exchanging gifts. Similar to Secret Santa, the gifter–giftee roles are typically assigned at random, which, in the days of yore involved putting names in a hat and taking random draws until no one drew their own name. (Which, and I bet you didn’t expect this here – at least I didn’t – takes about $e$ times for sufficiently large groups. More about this later.)

Perhaps it was because during some years, some people replaced all of the names in the hat with their own (not looking at anyone in particular, although their name may start with ‘D’ and ends in ‘ad’). Or perhaps it simply became harder and harder to get everyone in the same place for the ‘lottery,’ but eventually our family’s tradition abandoned the hat, in lieu of a cloud-based solution for generating pseudorandom numbers.

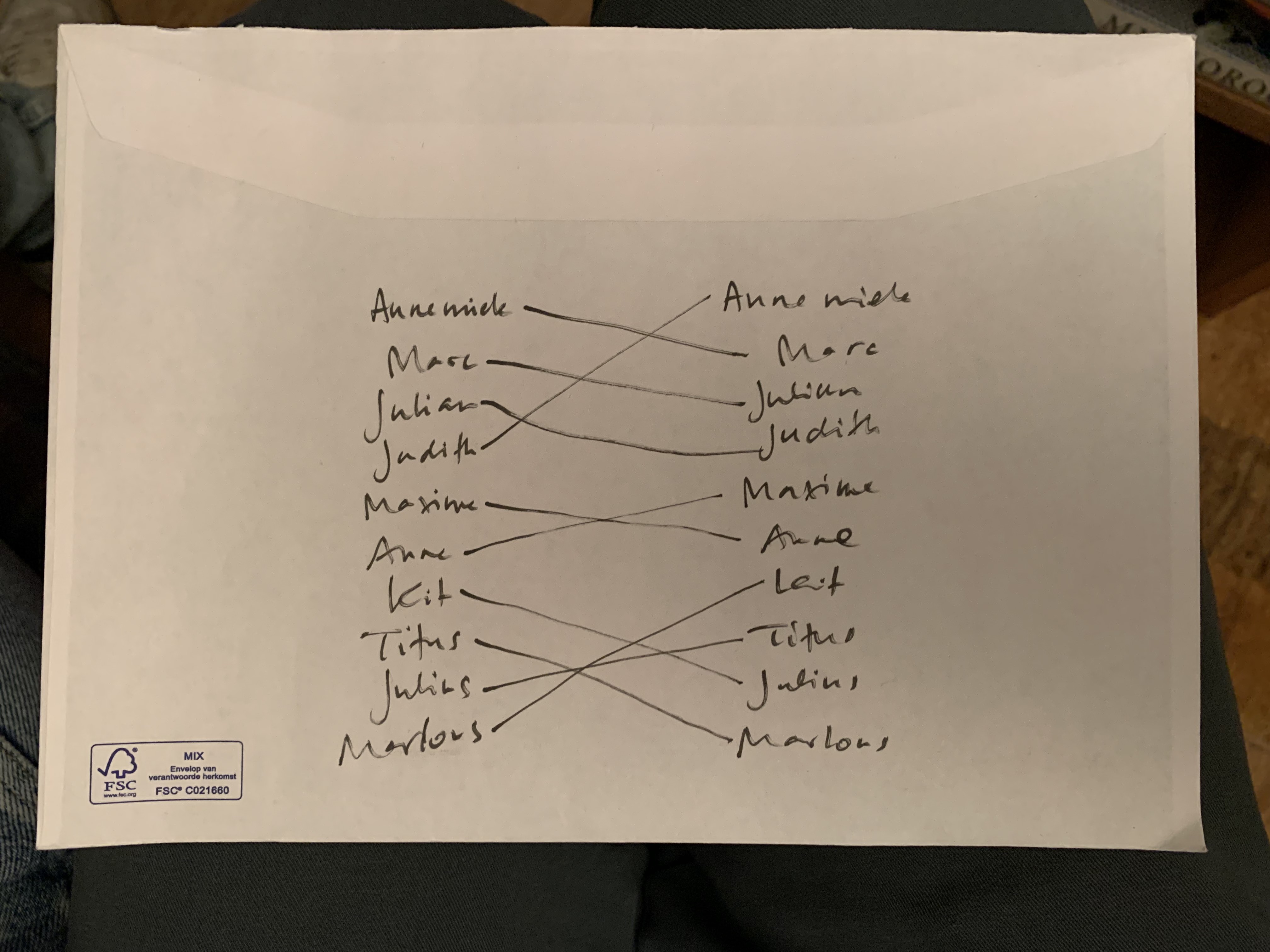

The day after this year’s iteration, my partner wanted to reconstruct the gifter–giftee graph, and ended up with the following:

The left and right columns correspond to the gifter and giftee, respectively. We can also draw this as a directed graph, and, if the back-of-the-envelope calculation wasn’t convincing enough, this immediately shows that in fact there wasn’t a single group playing Secret Santa this year, but that instead there were three!

“What a coincidence!” we rejoiced, and we wondered how likely it is for a group where each member is randomly assigned another member (different from themselves) to break up into a bunch of subgroups like this. It turns out, though, that this is pretty likely, especially if the group is large. In fact, below we’ll find that in our case with $N = 10$ participants, the chance of getting such a graph without subclusters is about 27.18%. Wait — could that be $e/10$?

But first, some intuition. How many unique, clusterless graphs are possible given $N$ participants in a Secret Santa game? We can think of this problem as having to draw a continuous chain that sequentially connects all the participants. The first person to draw a name has $N-1$ options (everyone excluding themselves). The second person, who, to enforce continuity, we define to be the name drawn by the first participant, has $N - 2$ valid options: anyone but themselves and the first person. This continues until we reach the last player, and multiplying all of this together yields $(N-1)(N-2)\cdots 1 = (N - 1)!$ possibilities.

Any other valid graph will feature subgraphs, and these are numerous. For instance, there are $\frac{1}{2}\binom{10}{5} = 126$ ways to divide a group of 10 into two subgroups of 5 (note the factor $1/2$ to avoid double counting). By the same arguments given above, there are $4! = 24$ ways to loop through these subgraphs without breaking them, which means we have $126 \cdot 24^2 = 72\,576$ unique distributions of names.

If we add up all of the possible ways in which the group can be divided, and multiply them with the appropriate binomial coefficients, we get the total number of possible Secret Santa games. Doing this is a fun exercise for another time; for now we’ll have to make do with the knowledge that this number is called the subfactorial, which counts the number of derangements (permutations in which no element is left in its original position, which amounts to the condition that no player can draw their own name). Interestingly enough, the subfactorial is denoted by $!N$, and can be defined as

\begin{equation} !N = N! \sum_{i = 0}^N \frac{(-1)^i}{i!}, \end{equation}

in which the careful reader can recognize the $N^\mathrm{th}$-order series expansion of $e^x$ evaluated at $x = -1$. A consequence is that (for large $N$), we can approximate the subfactorial as $!N \approx N!/e$.

And now for our final trick: if we draw a random graph we have $!N$ candidates, out of which we know $(N - 1)!$ to be contiguous. This means that the chance of drawing a contiguous one is

\begin{equation} \frac{(N-1)!}{!N} = \frac{1}{N \sum_{i = 0}^{N} (-1)^i/i!} \approx \frac{e}{N}, \end{equation}

which, for $N = 10$, is indeed approximately $e/10$.